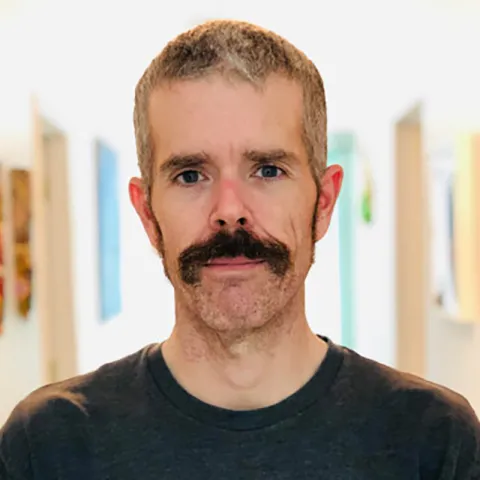

By the time he became an emergency nurse in 2019, the chaos of the emergency department didn’t feel too daunting to Kelly Edwards, MSN, APRN, CEN, FP-C. At that point, the North Carolina native was in his 40s. He had already worked for years as a paramedic and flight paramedic, including as a volunteer for Haiti Air Ambulance.

If anything, Edwards said the emergency department has a couple of perks compared to being a flight paramedic.

“I used to tell people, ‘The big difference is: Working in the hospital, you have artificial lighting and controlled temperature,’” he said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Edwards was splitting his time between emergency nursing and flight paramedic work. As he started feeling burnt out and overwhelmed, Edwards said he got an offer to join Haiti Air Ambulance full-time.

He took the job. Now, going on his sixth year with Haiti Air Ambulance, Edwards said he’s a flight paramedic, RN, and clinical education coordinator. On any given day, that means he could be in a helicopter as a flight clinician, on the ground helping a partner agency with clinical work or providing remote care to patients anywhere in the country.

Edwards has also worked with local nursing schools to advance the specialty in Haiti. Initially, these efforts were geared toward education, credentialing, and licensure, but those goals have shifted amid waves of political turmoil in Haiti.

In 2021, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated. Since then, the nation of roughly 12 million people has had no president, and warring gangs have increased their control over Port-au-Prince, the capital. The government’s last remaining democratically elected officials left the country in 2023. It’s unclear when the next national elections will take place.

“The health infrastructure, which wasn’t great before all this happened … has really crumbled,” Edwards said. “A lot of our partner agencies that we worked with, like Doctors Without Borders, have had to shutter most of their operations inside Port-au-Prince because of the gang violence. Their hospitals, their clinics have been burned, destroyed, and looted by the gangs.”

Given that insecurity, Haiti Air Ambulance – which is funded primarily through donations – has downsized its operation in the country. As Edwards pointed out, they can only transport patients to a hospital if it’s still operational. When transporting a patient is out of the question, Edwards has helped deliver supplies, vaccines, and even teams of physicians and nurses to clinics and villages across Haiti.

Advocacy and education efforts are still taking place in Haiti, though those, too, have changed by necessity. Edwards said advocacy is now less about credentialing and more about ensuring the basic safety of health care professionals. Education is more focused on teaching nurses CPR, first aid, and tips for taking care of themselves as they work in such trauma-filled environments.

Haiti Air Ambulance’s efforts have also extended beyond Haiti’s borders. In 2025, Edwards’ team was leading some of the disaster relief efforts in Jamaica following Hurricane Melissa.

“From about November 10 to December 4, we coordinated most of the medical disaster relief that took place in Jamaica,” he said. “Over that time period we did 240-something flights by helicopter, transporting equipment, personnel, medicine, and food all over the country.”

Although Edwards spends most of his time in Haiti, he returns home to rural Georgia for about three to four weeks at a time. During those trips, he fills shifts at some of the local emergency departments, including at Brooks County Hospital in Quitman, Georgia.

When asked, Edwards said it’s difficult to summarize why exactly he’s kept coming back to Haiti Air Ambulance.

“We all entered this profession to do meaningful work by helping others, but the nature of healthcare work in the emergency room leaves many of us burned out and unfulfilled,” he said. “In Haiti, I find the meaningful work and intrinsic reward that keeps me fulfilled and motivated in my career.”